Science and medical reporting, including on Covid-19, should make sense to laypeople and policymakers to bring about greater awareness and informed decision-making which results in meaningful change. Use this handy guide to cover science and health better.

By Boo Su-Lyn, Editor-in-Chief of CodeBlue

Good science writing, including reporting on Covid-19, must be clear and comprehensible to the general public. This means defining medical/scientific jargon and, more importantly, explaining the implications of your report – i.e., what does your story mean?

Common mistakes to avoid

When reporting on Covid-19 and vaccination, understand the difference between various indicators and explain them clearly:

- Only one dose vs “at least” one dose: The number of people who received their first dose may include some who received their second dose in two-dose vaccine regimens. Hence, the number of people who received their first dose may be described as the number of people who received “at least one dose”.

- Avoid sparking vaccine hesitancy: It’s tricky to maintain the balance between reporting facts and inadvertently creating vaccine hesitancy, especially when reporting on issues like breakthrough infections or severe side effects after vaccination. As a rule of thumb, try to avoid sensational headlines. If the headline is somewhat negative – for example, “vaccine breakthrough cases rise”, balance it with a standfirst or social media caption that highlights most infections being mild. There’s no hard and fast rule – use your judgment.

- Missing context: Always put things in context. For example, when reporting about a country’s high vaccination rate, check it against other countries. Bear in mind that many developed countries have already vaccinated a far bigger proportion of their populations, hence their vaccination rates may be or are expected to slow.

- Avoid xenophobia: As Covid-19 doesn’t discriminate, reporting on the epidemic and vaccination should avoid casting any ethnic, occupational, or other group in a negative light or as a so-called source of infection.

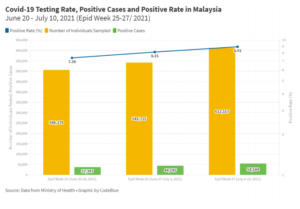

- Epidemic: Avoid headlines like “Covid-19 cases rise/decline” or saying that a particular area is the “worst-hit” based on the absolute number of Covid-19 cases. Put official case statistics in context. For example, Covid-19 cases may decline because less testing was conducted, but the positive rate remains high above 5%, which indicates that the epidemic may not actually be improving.

In terms of the severity of outbreaks in certain areas, compare incidence rates rather than absolute case numbers (the number of new cases divided by the population of an area multiplied by 100,000 = cases per 100,000 population). The same can be done when reporting on Covid-19 deaths. Using incidence or death rates enables equal comparison across districts/states/countries of different population sizes.

- Positive rate: WHO recommends a maximum 5% positive rate (the number of positive cases divided by tests multiplied by 100) as an indicator that an outbreak is under control. Hence, a decline in Covid-19 cases may not reflect the true picture of an epidemic if positive rates remain high above 5%.

Useful terms

- Incidence rate: number of cases per population

- Positive rate: share of tests that are positive

- Case fatality rate: proportion of deaths out of cases

- Epidemic: an often-sudden increase in the number of cases of a disease exceeding normal expectations in a specific area or region

- Pandemic: an epidemic that has spread across several countries or continents

- Breakthrough infections: infections among people vaccinated against a particular disease

Interview tips for interviewing medical professionals/policymakers

- Details: Details make the story. When reporting on Covid-19 situations in hospitals, for example, include details or anecdotes that illustrate the severity of the crisis.

- Jargon: Explain medical/scientific jargon or terms.

- Implications: Explain the significance of what you’re reporting. For example, when reporting on vaccine breakthrough cases, the implication would be that herd immunity from vaccination might be impossible to achieve, or that non-pharmaceutical interventions are still needed despite vaccination.

- Challenge: Don’t be afraid to ask for evidence or the basis of what medical professionals/ policymakers to tell you, or to challenge their assertions based on your understanding of the issue you’re reporting. Remember that there is diversity of opinions on science.

- Context: Put your stories in context. For example, when reporting on a decline in a particular state’s Covid-19 outbreak amid high vaccination rates, if the state has suffered previous outbreaks with much higher incidence rates than average, natural immunity from infection should also be pointed out.

- Qualifications: Not all medical professionals are the same. When reporting on specific issues like epidemic control, epidemiologists or public health specialists should be interviewed, not surgeons or general practitioners, for example.

Making sense of data (using Malaysian data as an example)

- Malaysia’s Covid-19 epidemic may be growing as the positive rate increased despite increased testing. Typically, with more testing, one would expect to see a decline in the positive rate.

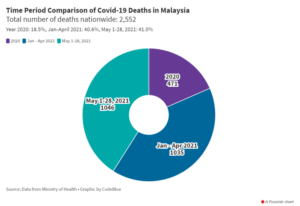

- The number of Covid-19 deaths in Malaysia in the first four months of 2021 was more than double the total deaths in the whole year of 2020. Things were worse in May 2021 that saw more Covid-19 deaths in 28 days compared to four months from January-April 2021.

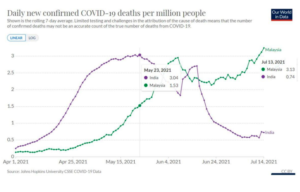

- Malaysia’s daily new Covid-19 deaths per capita exceeded, since July 13, 2021, the peak in India back on May 23.

Best practices

- What does your story mean? What are the implications of your story on public policy related to health or science?

- Multiple sources if anonymous: When using anonymous sources, be sure to interview at least three, if possible, to ensure a representative and accurate picture.

- Get the other side: This is especially crucial when your report is based on anonymous sources. For example, if health care workers talk about a worsening Covid-19 crisis in their facility, corroborate their accounts with hospital administrators or health officials. Even if authorities don’t respond, you must ensure that you have at least contacted them for their right of reply.

- Triple-check data: For data stories, triple-check data cited in your reports, including checking data in graphics used and the raw data. Mistakes may occur in reporting or in raw data entry.

- Put things in context: Context matters. For example, when reporting on the Covid-19 epidemic, explain any rise or decline in daily infections in the context of testing and positive rates.

- Build relationships: Like any other field in journalism, in science/medical writing, it is equally important to build relationships with people that you report on, for example the medical fraternity or policymakers involved in science/health, so that you can get exclusives or breaking stories.

Story ideas

- Data stories: Compare the Covid-19 epidemic/vaccination program in your country to other countries. Global data is available on org. For local stories, look at official data and think of ways to explain trends that are not explicitly spelled out by the government.

- Talk to people: Don’t just look for talking heads/ experts/ doctors. Talk to ordinary people on the ground, including non-medically trained people, to find out what’s really happening.

- International trends: In a pandemic, what happens globally affects us locally. For example, when international reports broke about the European Union’s vaccine passport not recognizing Covishield, you can find out directly from EU authorities on whether they have similar restrictions on vaccines used in your country.

Final notes

As a science writer, you should be a subject matter expert. You’re not just a writer or reporter copying and pasting quotes from newsmakers. This means being familiar with the subjects you’re reporting on and being aware of international scientific findings or trends that may also have an impact on the country you’re reporting. You should be able to analyse and write about developments independently without needing to interview medical experts. Sometimes, though, interviewing scientists may be necessary to confirm whatever theory/hypothesis you have or provide a range of viewpoints.

Beyond writing stories for your organization, you can also use social media as a platform to highlight your stories or opinions on Covid-19/vaccination trends or other science-related issues. This will help solidify your reputation as a subject matter expert, where non-medically trained lawmakers may ask you for advice.

Posts should be succinct and contain main takeaways from the issue you’re writing about, and ideally be accompanied by graphics, as many people don’t really like reading long articles or watch long videos. See sample tweet here.

Useful resources

- https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

- https://covid19.who.int/

- https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/

- https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

You can also follow experts on Twitter for Covid-19 analysis:

- Eric Topol @EricTopol

- Eric Feigl-Ding @DrEricDing

- Dr Angela Rasmussen @angie_rasmussen

For the full presentation and slide decks for my science masterclass, Understanding endemic diseases: will Covid-19 ultimately become one?, please click below:

Understanding endemic diseases by Boo Su-Lyn [download PDF]

Standards of care for endemic Covid-19: rapid antigen tests empower people by Dr Gerald Kost [download PDF]

Secrets to better science writing by Boo Su-Lyn [download PDF]

Boo Su-Lyn is the editor-in-chief of CodeBlue, a health news website based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. CodeBlue is an independent editorial programme of the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy.